Celebrating Chinese New Year as a Malaysian ‘banana’

Chinese New Year is a festivity that the Chinese community look forward to each year, be it the joy of receiving ang pau, tucking into large feasts of traditional Chinese food, and even eavesdropping on the occasional family quarrel at reunion dinner that usually becomes the family gossip of the year.

While most people would experience the excitement and joy of the New Year, feelings of dread, reluctance, and shame well up in me when I have to visit relatives on my mother’s side, who are more traditionally Chinese.

That’s because I fit the identity often described as a ‘banana’ – someone who is ethnically Chinese, but raised with English as a first language, while not being fluent in Mandarin or any of the other Chinese dialects. Figuratively speaking, it’s a yellow-skinned person having the soul of an ang moh.

Here’s my story:

Losing touch with my mother tongue

With my father as the single parent, I naturally grew up in an English-speaking household, as he was English-educated. Through his upbringing, I was exposed to Western values and culture, more so than my Chinese counterparts.

Although I attended a Chinese primary school, learning Mandarin was difficult as I had no one to practice speaking the language with. By Standard 3, my classmates could read textbooks fluently, while I struggled, stumbling every few words as the vocabulary became more complex.

Me attending Chinese primary school.

Me attending Chinese primary school.

I eventually gave up on my Chinese language studies in my final years of primary school, and performed poorly in my Mandarin tests during UPSR. After that, I enrolled in a national secondary school and discontinued my Chinese language studies entirely.

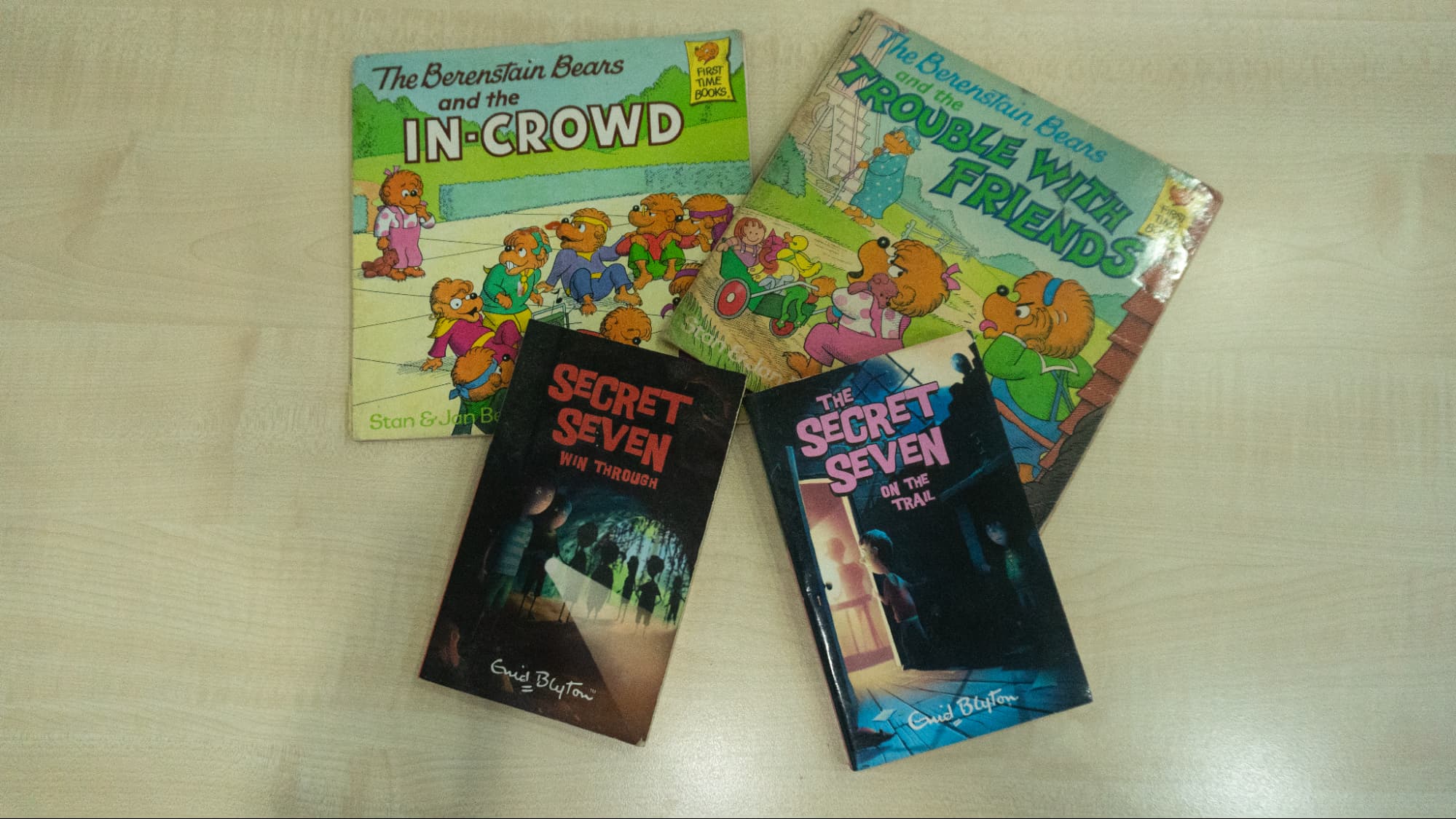

Meanwhile, my paternal uncle gifted me several boxes of Enid Blyton books, including her well-known The Secret Seven series, as well as popular American picture books like The Berenstain Bears. These books not only built a strong foundation for my English language skills but also deepened my interest in English books.

Additionally, having access to MTV channel on my TV meant I grew up listening to a wide range of 1990s–2000s American pop music. I became familiar with the English lyrics of songs from popular artists of the era like Michael Jackson, Kelly Clarkson, Avril Lavigne, and Mariah Carey.

Image credit: Brooklyn

In contrast, my classmates at Chinese school were immersed in local Chinese comics like 哥妹俩 (Kokko & May) and 小班长 (Little Monitor), and much of class conversation revolved around the latest Mandopop songs by artists such as Jay Chou, JJ Lin, and S.H.E.

Unfortunately, my interests in English books and American pop music didn’t align with typical classroom conversations, leaving me feeling excluded from many discussions with friends.

Over time, these experiences ultimately led to my falling out of learning Mandarin, and made it harder for me to connect with certain aspects of Chinese culture.

The awkward Chinese New Year experience with my mother’s family

Since my parents are divorced, Chinese New Year visits are split between their households. While conversations with my father’s side are always in English, the same cannot be said for my mother’s side.

Mini me & my maternal grandmother.

Image credit: Brooklyn

In Mandarin, relatives are addressed using different terms depending on whether they come from the paternal or maternal side. This often leads to awkward moments when I have to greet my many uncles and aunts, whose specific titles I rarely remember since I only see them once or twice a year.

Moreover, family conversations would mostly be in Mandarin or Hakka, and while I can understand most of it, I still require my mother’s help in translating certain words and phrases. I was also the only cousin who grew up away from my mother’s hometown in Melaka, making it hard for me to interact with and grow close to my cousins and immediate relatives.

While my immediate family is accommodating of my poor Mandarin proficiency, talking slowly in the language and translating conversations for me, some of my distant relatives aren’t always as understanding.

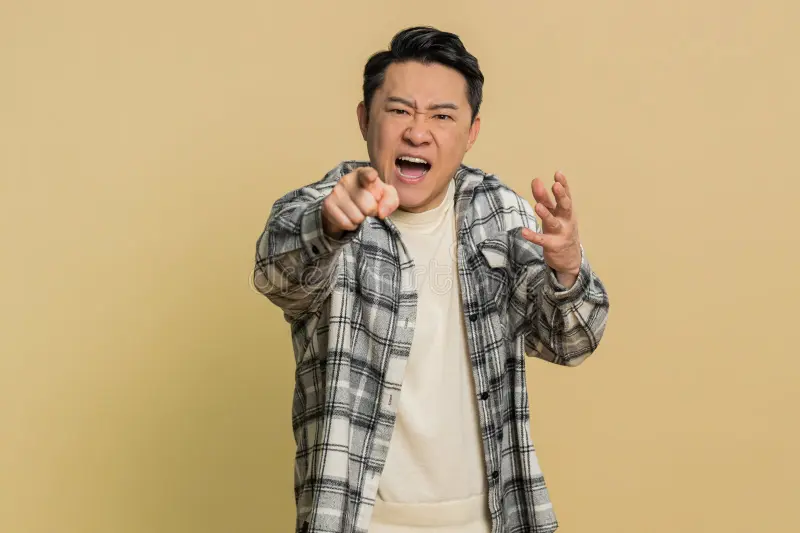

Image (for illustration purposes only) credit: Dreamstime

On one occasion during Chinese New Year, I greeted a distant uncle in English, and he took offence, responding with harsh comments like, “Why are you speaking in English? You’re a failure to your own race if you can’t even speak your mother tongue fluently”.

He reprimanded me in a secluded corner of the house, unnoticed by others. Though I wanted to defend myself, I didn’t want to spill any bad blood, so I silently endured his harsh words.

But those words dampened my spirits then and have, ever since, cast a shadow over the otherwise joyful celebrations of Chinese New Year.

Speaking another language does not completely erase your ethnicity or culture

While I can still hold a conversation in Mandarin and order food at a Chinese restaurant, I’m far more comfortable speaking in English or Malay in my daily life.

These days, I simply endure whatever comments my relatives make, whether about my relationship status, salary, or limited Mandarin proficiency, so as to not spoil the Chinese New Year celebratory mood. Because, after all, being fluent in a language different from my mother tongue does not diminish my ethnicity or culture any less than those who speak the language.

So, to all the ‘bananas’ who have experienced harsh remarks and awkward moments for not grasping your mother tongue, you’re definitely not the odd one out – even though it may feel and seem like it at reunion dinners.

Gong Xi Fa Cai, and Happy Chinese New Year to all who celebrate.

Cover image adapted from: Brooklyn

Photography by Brooklyn & Xin Yee.